This phase will have us reading about Jesus’s life in the gospel of Luke, the formation of the Church in Acts, and walk through the theology found in Paul’s letters that the Church needs to know about and live out the eternal life given by grace through faith in Jesus.

Below, you’ll find brief synopses of each book in this phase to help you understand the scope of the book and most importantly, how it fits into the full Story of the Bible.

When you click on each day’s link, you will find a link to audio, a summary of the chapter, a key verse from the chapter, and opportunities for reflection and outreach.

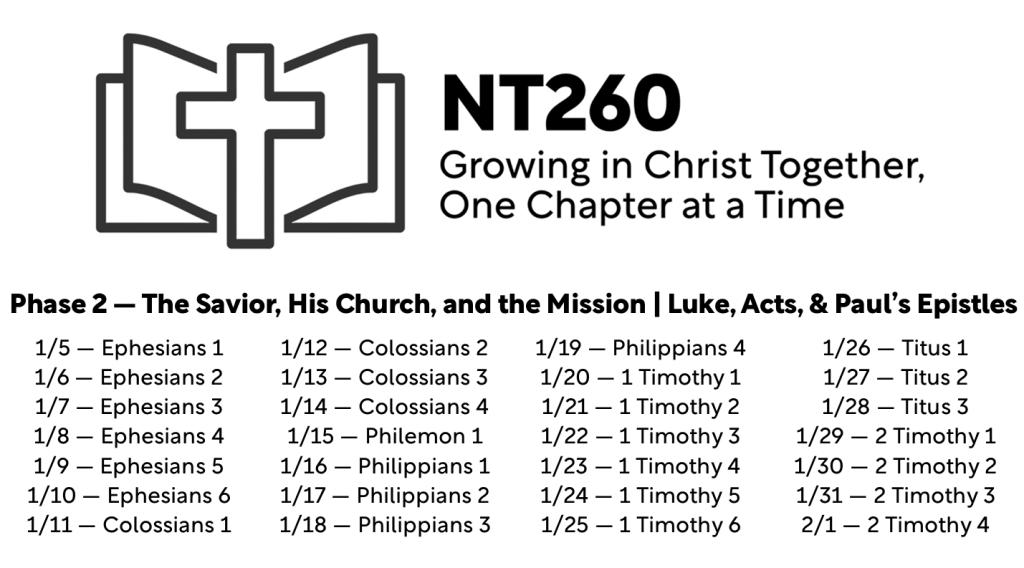

We’re moving into Paul’s epistles, which we’ll go through chronologically rather than in the order they appear in our Bibles.

Ephesians

Ephesians is a letter written by the apostle Paul around A.D. 60–62 while he was imprisoned in Rome (Ephesians 3:1, 6:20; Acts 28). Although traditionally addressed “to the Ephesians,” the letter was likely intended as a circular letter for several churches in the region of Asia Minor, with Ephesus as its primary hub (Ephesians 1:1). Paul had spent several years ministering in and around Ephesus (Acts 19:10), but the letter’s broad and impersonal tone suggests he is addressing a wider group of believers. Rather than responding to a specific crisis, Paul writes to remind the church who they are in Christ and how they are to live in light of God’s saving work.

At the heart of Ephesians is the breathtaking truth that God is uniting all things in Christ (Ephesians 1:9–10). Paul begins by praising God for the spiritual blessings believers have received “in Christ,” including election, redemption through Christ’s blood, forgiveness of sins, and the sealing of the Holy Spirit (Ephesians 1:3–14). He then reminds readers of what God has done for them personally: though they were once dead in sin, God made them alive by grace through faith—not by works (Ephesians 2:1–10). This saving grace does more than rescue individuals; it creates a new people. In Christ, Jews and Gentiles who were once divided are now reconciled to God and to one another, forming one new humanity and one household of God (Ephesians 2:11–22).

In the story of the Bible, Ephesians lifts our eyes to the cosmic scope of redemption. What God promised throughout the Old Testament has come to fulfillment in Jesus Christ, and the church now stands at the center of God’s plan to display His wisdom and grace to the world—and even to the heavenly powers (Ephesians 3:10–11). Christ reigns over all authority and power, and the church is His body, filled by Him and united under His headship (Ephesians 1:20–23). This new covenant people exists by grace alone and lives for the glory of God, awaiting the final consummation of all things in Christ.

The second half of Ephesians shows how these glorious truths shape everyday life. Because believers have been called into one body, they are urged to walk in unity, holiness, love, and wisdom (Ephesians 4:1–6, 5:1–2). Paul applies the gospel to relationships in the home, the church, and the world, showing what it looks like to live as those who belong to Christ (Ephesians 5:21–6:9). The letter closes with a call to stand firm in spiritual battle, clothed in the armor God provides, relying on His strength rather than our own (Ephesians 6:10–18). Ephesians reminds us that the church does not create its identity—it receives it from Christ—and then lives it out for His glory until He brings all things to completion.

- January 5 — Ephesians 1

- January 6 — Ephesians 2

- January 7 — Ephesians 3

- January 8 — Ephesians 4

- January 9 — Ephesians 5

- January 10 — Ephesians 6

Colossians & Philemon

Colossians is a letter written by the apostle Paul, with Timothy alongside him, to believers in the small city of Colossae (Colossians 1:1). Paul likely wrote during his imprisonment, most commonly connected to his Roman imprisonment, around A.D. 60–62 (Colossians 4:3, 10, 18; Acts 28). The letter was carried by Tychicus, and Onesimus traveled with him (Colossians 4:7–9), linking Colossians closely with Philemon and placing it in the same “Prison Letters” cluster as Ephesians. Paul had not personally visited Colossae (Colossians 2:1). Instead, the church seems to have been founded through the ministry of Epaphras, who likely came to faith during Paul’s years in Ephesus and then returned home to proclaim the gospel (Colossians 1:7, Acts 19:10).

Paul writes because a dangerous teaching was unsettling the church and threatening their confidence in Christ. While scholars debate the exact label for the error, the letter itself makes clear what was happening: voices were pressuring believers to look beyond Jesus for spiritual “fullness,” protection, or maturity—through additional spiritual intermediaries, mystical experiences, and a regimen of rules or ascetic practices (Colossians 2:8, 16–23). There are Jewish elements (festivals, Sabbaths) and spiritual/angelic elements (“worship of angels”), along with the sense that special insight or extra steps were needed to be truly secure (Colossians 2:16–18). Epaphras was so concerned that he sought Paul’s help, and Paul responds by pulling the church back to the center: Christ is enough, and nothing must be allowed to diminish His supremacy or the believer’s identity “in Him” (Colossians 2:9–10).

In the overall story of the Bible, Colossians declares with stunning clarity who Jesus is and what His saving work has accomplished. Christ is the image of the invisible God, the creator and sustainer of all things—visible and invisible—and the One through whom God will reconcile all things to Himself (Colossians 1:15–20). He is not one spiritual option among many; He is Lord over every power and authority, and in Him the fullness of deity dwells bodily (Colossians 2:9–10, 15). Because believers are united to Christ, they share in His death and resurrection life: they have been delivered from darkness, forgiven, and brought into the kingdom of the beloved Son (Colossians 1:13–14, 2:11–14). That means they do not need other mediators, rituals, or spiritual add-ons to make them complete—God has already made them full in Christ (Colossians 2:10).

Colossians also shows how a Christ-centered gospel produces a Christ-shaped life. Since believers have been raised with Christ, they are called to set their minds on the things above, put off the old patterns of sin, and put on the new virtues that reflect the character of Jesus—compassion, kindness, humility, patience, love, and thankful worship (Colossians 3:1–17). Paul brings that transformation into everyday relationships and households, showing that the lordship of Christ reaches into the ordinary places of life (Colossians 3:18–4:1). In the end, Colossians is both a warning and an encouragement: don’t be captured by man-made religion or fear-driven spirituality, but hold fast to Christ—the Head of the church, the Savior who reconciles, and the victorious Lord who is sufficient for His people in every way (Colossians 1:18–20, 2:19).

- January 11 — Colossians 1

- January 12 — Colossians 2

- January 13 — Colossians 3

- January 14 — Colossians 4

Philemon is a short, one-chapter personal letter from the apostle Paul (with Timothy named alongside him) to a believer named Philemon, a leader in Colossae whose home hosted a local church (Philemon 1–2). It was written during Paul’s imprisonment, most likely in Rome, around A.D. 60–62, at roughly the same time as Colossians, and it travels with the same delivery team—Tychicus and Onesimus (Colossians 4:7–9). That connection matters: when the church in Colossae gathered to hear Colossians read aloud—Christ’s supremacy, the believer’s new identity “in Him,” and the call to put on love and forgiveness (Colossians 1:15–20, 2:9–14, 3:12–14)—Philemon would have heard those truths first, and then received a second letter that applied them to a real situation in his own home.

The situation centers on Onesimus, who had wronged Philemon in some way (likely by running away and possibly causing financial loss), but who encountered Paul and was converted to Christ (Philemon 10, 18). Paul then sends Onesimus back—not merely to “return property,” but to pursue reconciliation shaped by the gospel. The heart of Paul’s appeal is that the gospel transforms people and relationships: Onesimus, once “useless,” has become truly “useful” (Philemon 11), and Philemon is urged to receive him “no longer as a bondservant but more than a bondservant, as a beloved brother” (Philemon 16). Paul could have commanded, but for love’s sake he appeals, even offering to cover any debt Onesimus owes (Philemon 8–9, 18–19). In the story of redemption, Philemon is a small letter with a big message: because Christ has forgiven and reconciled us to God, believers are called to extend that same grace toward one another—letting Jesus be “over us” not only in doctrine, but in everyday obedience, forgiveness, and restored fellowship (Philemon 15–17; cf. Colossians 3:13).

- January 15 — Philemon

- Additional Resources for studying Philemon:

Philippians

Philippians is a warm, joy-filled letter written by the apostle Paul to the Christians in Philippi, a Roman colony in Macedonia and the first place in Europe where Paul established a church (Acts 16:12–40). From the beginning, this congregation had a special partnership with Paul: Lydia was the first convert, the Philippian jailer was brought to faith through God’s dramatic deliverance, and the church consistently supported Paul’s gospel work through prayer and generous giving (Acts 16:14–15, 33–34; Philippians 1:5, 4:15–16). Paul writes while imprisoned—most likely in Rome around A.D. 60–62—since he mentions the “praetorium” and “Caesar’s household,” and he speaks as though his case could soon end either in release or death (Philippians 1:13, 20–23; 4:22; cf. Acts 28:16, 30–31). The immediate occasion includes the Philippians’ gift sent through Epaphroditus and Paul’s desire to send news back—especially that Epaphroditus recovered from a serious illness and is returning to them (Philippians 2:25–30, 4:10–18).

Even so, Philippians is far more than a thank-you note. Its heartbeat is encouragement—calling believers to live as citizens of a heavenly kingdom in the middle of a proud Roman culture (Philippians 1:27, 3:20). Paul shows what that looks like through repeated themes of gospel-centered unity, humble service, steady joy, and faithful perseverance even in suffering (Philippians. 1:27–30, 2:1–4, 4:4–7). The centerpiece of the letter is the stunning portrait of Jesus in Philippians 2:5–11: though truly divine, Christ humbled Himself, took the form of a servant, and obeyed to the point of death on a cross—therefore God highly exalted Him so that every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord (Philippians 2:6–11). That Christ-shaped pattern then becomes the model for the church: Paul points to Christ first, and then to living examples like Timothy and Epaphroditus, urging the Philippians to put others first and to labor together for the gospel (Philippians 2:19–30).

Philippians also makes clear that spiritual growth is not passive. Paul presses the church to keep moving forward—never settling into spiritual complacency—because the gospel is too glorious and the world too dangerous for “coasting” (Philippians 1:25, 3:12–16). He warns them about false teachers who would replace Christ with confidence in the flesh, reminding them that righteousness comes through faith in Christ, not law-keeping or religious status (Philippians 3:2–9). Yet even while calling them to effort—“work out your own salvation with fear and trembling”—Paul anchors their confidence in God’s active grace: “for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Philippians 2:12–13). In short, Philippians teaches a church how to live with deep joy and deep humility, holding tightly to Christ, standing together in unity, and pressing on until the day when their King is fully revealed (Philippians 1:6, 10; 3:14, 20–21).

- January 16 — Philippians 1

- January 17 — Philippians 2

- January 18 — Philippians 3

- January 19 — Philippians 4

1 Timothy

First Timothy is a pastoral letter from the apostle Paul to his younger coworker Timothy, whom Paul calls his “true child in the faith” (1 Timothy 1:2). Timothy had traveled and ministered alongside Paul for years (Acts 16:1–3, 19:22; Philippians 1:1), and at the time of this letter Paul had left him in Ephesus to help strengthen the church and confront serious problems there (1 Timothy 1:3). Ephesus was a major and influential city, and Paul had already warned that dangerous teachers would arise and draw people away from the truth (Acts 20:29–30). First Timothy addresses that exact kind of threat: teaching that sounded religious but produced confusion, pride, quarrels, and greed rather than love and godliness (1 Timothy 1:4–7, 6:3–10). Although some modern scholars dispute Paul’s authorship, the letter plainly names Paul as its author (1 Timothy 1:1), reflects a strong personal and autobiographical tone, and was received as Pauline and authoritative very early in the church’s life.

The timing likely fits after Paul’s first Roman imprisonment (Acts 28:16, 30–31). On the traditional understanding, Paul was released, continued mission work, and then later faced a second imprisonment that led to his death. In that window, 1 Timothy would fall in the early-to-mid 60s (often dated around A.D. 62–64), written from an unknown location while Timothy labored in and around Ephesus (1 Timothy 1:3, 3:14–15). Paul hopes to come to Timothy, but he writes so Timothy will know “how one ought to behave in the household of God,” which is the church (1 Timothy 3:14–15). In other words, this is not a detached manual—it’s an urgent, fatherly charge to protect the gospel and shepherd God’s people well (1 Timothy 1:18, 6:20–21).

A key thread through the whole letter is that right doctrine produces real-life change. Paul is not mainly interested in winning arguments; he is concerned that the true gospel leads to love from a pure heart, a good conscience, and sincere faith (1 Timothy 1:5). That’s why he keeps returning to the contrast: false teaching fuels empty speculation and moral collapse, but sound teaching produces visible godliness (1 Timothy 1:3–7, 4:6–16, 6:3–14). Paul anchors this in the message of salvation itself—God’s mercy to sinners in Christ (1 Timothy 1:12–16), the one Mediator who gave Himself as a ransom (1 Timothy 2:5–6), and God’s desire for the gospel to go to all peoples (1 Timothy 2:1–7, 4:10). Because the gospel is true, the church must be shaped by it in worship, leadership, relationships, and everyday conduct.

So Paul gives Timothy practical instructions that flow from the gospel: guard the church’s public worship with prayer, unity, and holiness (1 Timothy 2:1–15); appoint qualified overseers and deacons whose lives display maturity and self-control (1 Timothy 3:1–13); train for godliness and model faithful ministry (1 Timothy 4:6–16); honor and care for people wisely—older and younger, widows, elders, and even slaves—so that love and integrity mark the congregation (1 Timothy 5:1–6:2). He also warns against greed and calls believers to contentment, generosity, and a firm grip on “the faith” (1 Timothy 6:6–19). In the end, 1 Timothy is a clear call to protect the purity of the gospel and to show its power in the day-to-day life of the church—so that God’s household reflects God’s character and Christ’s saving work (1 Timothy 3:15–16).

- January 20 — 1 Timothy 1

- January 21 — 1 Timothy 2

- January 22 — 1 Timothy 3

- January 23 — 1 Timothy 4

- January 24 — 1 Timothy 5

- January 25 — 1 Timothy 6

Titus

Titus is a short pastoral letter from the apostle Paul to his trusted coworker Titus (Titus 1:1, 4). Like 1 Timothy, it’s written to a ministry partner who is helping establish and stabilize young churches, and it strongly links sound faith with godly living—belief and behavior belong together (Titus 1:1, 2:11–14). Though some modern scholars question Paul’s authorship, the letter clearly identifies Paul as its author (Titus 1:1), fits well with Paul’s theology, and was received early in the church as a Pauline, authoritative writing.

The letter is typically dated to the early-to-mid 60s (around A.D. 62–64), during the period after Paul’s first Roman imprisonment and before a later imprisonment that ended in his death (cf. Acts 28:30–31). Paul had recently ministered on the island of Crete and left Titus there to “put what remained into order” by appointing elders in the churches (Titus 1:5). Paul plans to meet Titus in Nicopolis (Titus 3:12), but in the meantime he writes with urgency and clarity, giving Titus marching orders for healthy church life.

A key reason for the letter is the presence of false teachers—especially those with a strong Jewish flavor (“the circumcision party”), who traffic in “myths” and distorted teaching while producing ungodly lives (Titus 1:10–16). Paul’s concern is not just their ideas but their fruit: they “profess to know God, but…deny him by their works” (Titus 1:16). In a culture known for disorder and immorality (Titus 1:12), that kind of “religion” would blend right in. Paul expects the gospel to do the opposite: to create a people whose lives make the message believable and beautiful (Titus 2:5, 8, 10).

So Titus gives a portrait of a healthy church. It starts with godly leadership—elders who are above reproach, able to teach what is true, and able to correct what is false (Titus 1:5–9). It includes firm handling of error and divisiveness (Titus 1:10–16, 3:9–11). And it presses the gospel into everyday life for everyone in the church—older and younger, men and women, and even servants—so that the church’s conduct “adorns” the doctrine of God our Savior (Titus 2:1–10).

At the heart of the letter are two gospel-rich summaries that show why Christian ethics matter. God’s grace has appeared in Jesus to save and to train His people to renounce ungodliness and live self-controlled, upright lives while waiting for Christ’s return—“our great God and Savior Jesus Christ” (Titus 2:11–14). And salvation is not earned by works, but comes by God’s mercy through the washing and renewal of the Holy Spirit—so believers devote themselves to good works as the fitting fruit of grace (Titus 3:4–8, 14). In short, Titus shows that the gospel doesn’t only rescue sinners—it reshapes communities, builds healthy churches, and sends believers into the world with a credible, compelling witness.

2 Timothy

Second Timothy is Paul’s final and most personal pastoral letter to Timothy (2 Timothy 1:1–2). Like 1 Timothy, it addresses ministry in and around Ephesus and the need to guard the gospel against error, but the tone is different: this is a “farewell” letter written with death in view. Paul is imprisoned in Rome again—this time not in relatively open house arrest (Acts 28:16, 30–31), but “chained like a criminal” and expecting execution (2 Timothy 2:9, 4:6–8). Most date it during Nero’s reign, likely in the mid-to-late 60s (about A.D. 64–67).

The heart of the letter is a bold call to persevere in the gospel despite suffering. Paul urges Timothy not to shrink back in fear, not to be ashamed of Christ or of Paul’s chains, and to be willing to suffer for the gospel by God’s power (2 Timothy 1:7–8, 12). Timothy is to guard “the good deposit” of sound teaching “by the Holy Spirit” (2 Timothy 1:13–14), pass that gospel truth on to faithful men who will teach others (2 Timothy 2:2), and do the steady work of ministry even in a hard season (2 Timothy 2:3–7, 4:5).

Because Paul knows time is short, he speaks with clarity about what will threaten Timothy and the church: people who quarrel about words, drift into irreverent babble, and distort the truth (2 Timothy 2:14–18), and a worsening climate of godlessness and opposition in the “last days” (2 Timothy 3:1–9). The primary safeguard is not novelty but Scripture. Timothy is to continue in what he has learned, because the Scriptures are able to make one wise for salvation through faith in Christ, and because “all Scripture is breathed out by God” and equips the servant of God for every good work (2 Timothy 3:14–17).

The letter culminates in Paul’s solemn charge: “preach the word…in season and out of season” with patience and careful teaching (2 Timothy 4:1–5), because a time is coming when many will not endure sound doctrine (2 Timothy 4:3–4). Then, in one of the most moving moments in the New Testament, Paul reflects on his own finished race and sure hope: he is being “poured out,” but he looks ahead to “the crown of righteousness” that the Lord will give to all who love Christ’s appearing (2 Timothy 4:6–8). Even as friends have scattered and only Luke remains (2 Timothy 4:10–11), Paul’s confidence is steady: the Lord will bring him safely into His heavenly kingdom (2 Timothy 4:18). Second Timothy is, in the end, a last word from a spiritual father: hold fast to Christ, treasure the Scriptures, proclaim the gospel, and endure—because Jesus is worth it, and His coming is sure.

Continue reading in our NT260 plan with Phase 3 — Persevering in the Last Day.

29 Comments